[ad_1]

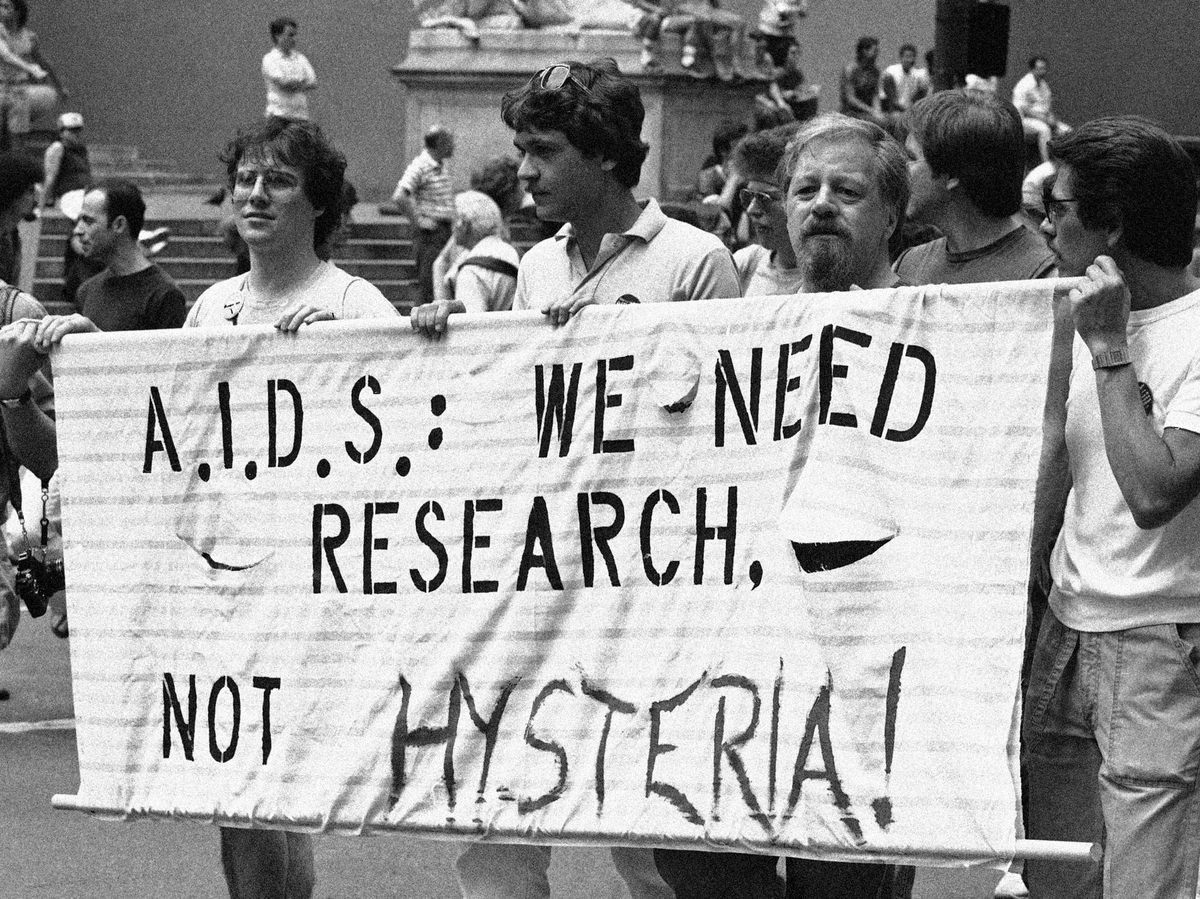

A gaggle advocating AIDS analysis marches down Fifth Avenue throughout the Lesbian and Homosexual Delight parade in New York, June 26, 1983.

Mario Suriani/Related Press

cover caption

toggle caption

Mario Suriani/Related Press

A gaggle advocating AIDS analysis marches down Fifth Avenue throughout the Lesbian and Homosexual Delight parade in New York, June 26, 1983.

Mario Suriani/Related Press

Within the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, concern and paranoia reigned. The virus, which was first reported within the U.S. in 1981, ravaged weak communities, and well being care staff caring for folks with HIV/AIDS confronted a backlash from household and neighborhood members who did not perceive how the virus was spreading.

In his podcast, “Blindspot: The Plague in the Shadows,” host Kai Wright revisits these early years, focusing specifically on populations which are ceaselessly ignored.

“The individuals who have been most affected [by the AIDS crisis] are sometimes additionally the individuals who have been most undocumented within the storytelling and least talked about,” he says. “And so we wished to return, we wished to inform among the tales that got here out of these communities.”

“Blindspot” goes inside a pediatric ward in Harlem, a drug market within the South Bronx and a girl’s jail in upstate New York, providing what Wright calls a “a street map of our social inequities and our bigotries” — in addition to a commentary on “political and financial selections about who’s expendable.”

Wright notes that well being care staff who cared for sufferers with HIV/AIDS did so at nice private value: “They weren’t thought-about heroes on the time. They have been thought-about pariahs.”

However, he provides, “Irrespective of the place you enter into this historical past, you discover these unimaginable human beings who did above and past, who led with love, to deal with different human beings when establishments have been failing. The pediatric ward of Harlem Hospital is exhibit A of that.”

Interview highlights

On the well being staff at Harlem Hospital who cared for pediatric sufferers with HIV/AIDS

It is a place the place we had seen huge public divestment from that hospital and from that neighborhood, interval, because the fiscal disaster in New York Metropolis within the ’70s by means of to when the epidemic emerged. On the time once they have been caring for these youngsters, they’d only a few sources. The stigma was uncontrolled. Individuals didn’t wish to have something to do with folks with AIDS, together with these youngsters. And the nurses and medical doctors on that ward used their very own cash, their very own time, to actually create a house for teenagers [with HIV]. …

They weren’t thought-about important staff. … They did this work with none of the applause. That is one other factor that has simply been so clear as we have reported, that is simply the injuries are recent, nonetheless, 40 years later.

On youngsters with HIV being separated from their mother and father

The fact of the epidemic amongst youngsters with HIV is that they’re people who find themselves being born with it, they usually’re being born with it as a result of, in lots of circumstances, their moms have been injection drug customers or had sexual relationships with injection drug customers, and have been HIV constructive. They have been poor girls of coloration. And this was the peak of the crack epidemic, we’ve got to recollect. And people infants have been being born with HIV, have been being separated from their mother and father, and have been residing and dying their entire lives on hospital wards. And Harlem Hospital is one place the place that was taking place, extra so than anyplace else within the nation.

On federal packages that ultimately got here by means of for folks with HIV/AIDS

A kind of actually essential items of coverage is the Ryan White CARE Act that is handed in 1990, and it stays a extremely essential a part of the American response to HIV. It funds care and therapy for poor folks, basically. And it’s notable that that regulation is called after Ryan White, a 13 yr previous boy who who acquired HIV by means of a blood transfusion, and he’s actually the epitome of innocence on this epidemic, proper? He’s the person who folks can say, … “You did not do something to carry this on your self.” And that framework from ’87 ahead – I might argue we’re nonetheless combating it right this moment – the concept, OK, we will begin to reply to this [health crisis], however just for the individuals who did not deserve it — for these drug customers, for these promiscuous homosexual males, for individuals who introduced this on themselves, for the moms of these youngsters at Harlem Hospital — they’re thought-about vectors of illness versus victims.

On how the conflict on medicine led to extra folks dying from HIV/AIDS

One of many issues that I believe folks do not wrap their heads round is there’s part of this epidemic that did not have to occur in any respect. The drug conflict is immediately liable for the epidemic amongst injection drug customers. At one level, half of all of the injection drug customers in New York Metropolis have been HIV constructive. That could be a direct consequence of the truth that, throughout the ’70s, there was a shift to saying, “OK, we’ll have a policing response to the heroin disaster.” And we, in plenty of states, together with New York, outlawed the possession of syringes. … And what that led to was the creation of capturing galleries. … And so folks would get collectively and share the identical needle in these capturing galleries. And it grew to become probably the most environment friendly ways in which HIV unfold on this planet was in these capturing galleries. And it led to these type of alarming numbers. That’s the drug conflict and the alternatives we made about cope with medicine immediately inflicting enormous quantities of loss of life.

After which when public well being began to give you the thought of … syringe alternate, which is one thing we’ve got now, it took so lengthy for that to really change into authorized. … There are explicit classes like that the place our bigotries, our punitive perspective in direction of people who find themselves in want have precipitated illness on this nation. And HIV is, sadly [an] wonderful instance for us to take a look at, to see that course of.

On some Black funeral properties refusing to bury individuals who died of AIDS-related diseases

The stigma was important sufficient that funeral properties refused to bury folks. … There grew to become an entire style of queer activism specifically that’s the AIDS funeral, as a result of folks must give you their very own methods to rejoice individuals who had been misplaced, as a result of if church buildings would bury somebody in any respect, they’d erase the whole lot about that individual’s life that they discovered shameful. They might erase the truth that they have been queer. They might erase the truth that they’d HIV. They might say they died of most cancers. They might say they died of tuberculosis, of issues aside from HIV, and so then within the act of burying them, dehumanize them. And that was a profound and actual a part of what was taking place, not solely within the Black neighborhood, however actually within the Black neighborhood.

Amy Salit and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Carmel Wroth tailored it for the online.

[ad_2]